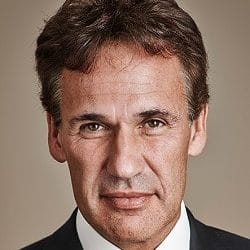

Susskind: Many lawyers and judges hanker for return to physical courts

A year of video hearings does not constitute “a lasting revolution in court service” but it has shown the potential for improving the justice system, Professor Richard Susskind has argued.

“The door has opened, if only slightly at this stage, to very different ways of resolving disputes,” he said.

“But the winds of conservatism blow briskly through the legal world and I am aware that many judges and litigators are quietly hunkering and hankering – hunkering down until the viral storm passes while hankering after a complete return to physical courts.”

But this will not deal with the challenges facing the systems – maintaining court service while the virus is still at large, coping with the growing backlog of cases and “tackling once and for all the access to justice problem”.

In a new introduction to the paperback edition of his book, Online Courts and the Future of Justice, the technologist said the experience since the pandemic hit suggested that “some – and probably many – legal disputes can indeed be handled remotely, often at lower cost, more conveniently, more speedily, and less combatively than in our traditional system”.

But this must be taken as a “tentative hypothesis”, one that needed to be challenged and tested systematically, with data captured and analysed.

It was an “overstatement” to claim that the transition to technology-based justice has been achieved, he stressed. Rather, the system has undergone a “huge unscheduled pilot”.

“We are at the foothills of the transformation in court services. The current array of remote courts are a valiant collection of ad hoc services but much work and investment will be needed to industrialise these efforts, to build court capabilities that are scalable, stable and, crucially, designed for use as much by lay people as by lawyers.”

More than this, the systems were still examples of automation rather than transformation. “We should be clear: dropping our current court system into Zoom is not, as some commentators like to intone, a ‘shift in paradigm’.”

At the same time, the legal profession has shown itself more adaptable than many might have thought and the level of satisfaction with video hearings was probably much higher than lawyers and judges would have anticipated “had they been asked before the crisis about the suitability of remote hearings”.

One aspect of the move online was the absence of direct mapping between the value of a case and its suitability for remote treatment.

Professor Susskind wrote: “When we ask what types of cases and issues can be settled by remote hearing, are we trying to determine when remote hearings can be said to be better than physical hearings; or as good as physical hearings; or not as good but ‘good enough’ (and when is good enough good enough?); or not as good but, with some investment and imagination, likely to be good enough, as good, or better?

“The commentary is currently silent on this issue, in so far as I can see. As a matter of urgency, this silence must be broken.”

In any case, Professor Susskind highlighted how his thinking about the future of courts has always extended far beyond video hearings.

“We are just warming up… In the coming years we will develop many online techniques for dissolving and diverting disputes.”

In his book, first published in late 2019, he called for the development of a “standard, adaptable, global platform for online courts” that could be rolled out to fortify access to justice around the world.

In the new introduction, he argued that court services globally should be planning and proceeding in three timeframes:

- In the short term, they should be stabilising and improving the ad hoc systems that are currently being used and so minimise the disruption to court services for the remainder of the crisis;

- In the medium term, they should “ensure that the experience of remote courts informs and, where appropriate, leads to changes in, any reform and digitisation programmes that were being pursued prior to the crisis”; and

- The long-term goal should be to “radically redesign our court systems and put in place a new configuration of people, processes, technologies, and physical spaces that is user-centred, technology-enabled, sustainable, accessible, and superior to what we have today”.

Professor Susskind explained that the third stage should be split into two workstreams. The first would involve a root-and-branch analysis of all judicial and court work, “break the work down into its component parts (tasks and activities), and, in light largely of the insights gained during the crisis, streamline and optimise each part”.

The second stream would be to conceive how the justice system would look “if we were able to start with a blank sheet of paper”.

Leave a Comment