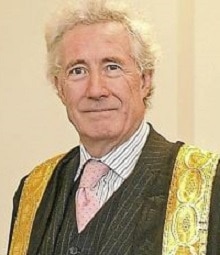

Legal specialisations are “essentially bogus”, Supreme Court judge Lord Sumption declared today as he urged practitioners to break out of their core areas and learn from other parts of the profession.

In a speech to a family law conference in London – an area in which he did not practice but which he found particularly insular – Lord Sumption said he did not regard law as comprising distinct bundles of rules, one for each area of human affairs.

“This is partly because no area of law is completely self-contained. Family law, like contract law, tax law, insolvency law or almost any other kind of law, has to be applied to a variety of different kinds of property and other legal rights…

“There is, however, a more fundamental reason for deprecating an excessively specialised approach. Law is, or at least should be, a coherent system. Of course, different human problems pose their own peculiar challenges, which the law must accommodate. But these challenges are not always as peculiar as people think.

“The practice of law, whether by judges or advocates, involves applying a range of common techniques and common instincts to a variety of legal problems. The common techniques are the objective construction of legislation and other written instruments, a respect for the body of decided case-law, and a sensitivity to changing attitudes in the world outside the law.

“The common instincts are those of the common law, which are essentially libertarian. They are founded on respect for the autonomy of the individual, a rejection of abstract moral duties unless traceable to some particular relationship or status, and a distrust of prescriptive rules without a clear social justification. These instincts operate within broad limits determined by our most basic collective ethical and moral values, in other words by public policy.”

Lord Sumption said he came to this question with “a certain amount of baggage”. He explained: “I have always taken the view that legal specialisations are essentially bogus. At the bar, I liked to trespass on other people’s cabbage patches. As a judge I do it most of the time.”

He acknowledged that “family law is in some respects special” as historically it was not part of the common law, but belonged to the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts. “Traditionally, its instincts have been very different from those of the common law. They were paternalist and protective.”

However, modern family law has moved a long way from this and “the last few years has seen a convergence between family law and the instincts of the common law”, with decisions on nuptial agreements, for example, effectively bringing the law of contract into the Family Division.

Lord Sumption continued: “One of the problems of specialisation is that it encourages a view of one’s subject which is too self-contained… In my experience, with a few notable exceptions, judges and advocates rarely search for principle beyond their own areas of specialised expertise.

“Advocates come into court with a library of familiar authorities which are part of the vernacular of practice in their area, without trying to relate them to any more fundamental legal principles. They take for granted rules of law which sometimes strike outsiders as distinctly odd but are too familiar to have struck practitioners that way.”

One of the advantages of an appellate system, he added, was that it allowed decisions from a specialised jurisdiction to be reviewed from the outside. “This permits a measure of cross-fertilisation between different areas of law, which for my part I think profoundly healthy.”

The phenomenon has been seen across many areas of law, Lord Sumption said, and “reflects the greater flexibility of the legal profession”.

“The division between the chancery bar and the common law bar, which was once absolute, has become almost imperceptible. Barristers, at least at the top end, are more inclined than they were to break out of their specialities. The family bar, I think, remains one of the more insular areas of practice. This deprives it of perceptions which would enrich it, as it has enriched other areas of law.

“Ultimately all of this depends on a willingness on the part of practitioners working in their core areas to look critically at familiar principles and relate them to what is happening elsewhere. Sometimes, distance lends enchantment.”

So there’s no room for specialists?

What about the benefits?

Obviously, an understanding of other areas helps, but don’t tell me that a shipping law specialist is not the best person to instruct on a shipping law case…unless it is a small claim and then someone well-versed in english contract law may do….but then it may be that a chancery barrister might be best…if equitable tracing is required…

Seems to me that specialism has its’ place as does general competency…it all depends on the case and the client, what is at stake etc.

The case for specialists is amply demonstrated in Patents cases but Family law practitioners already need to know enough Contract and Property law, some Tax law, some knowledge about Contact and Care proceedings…they are generally IMHO fully rounded.

Family law cases are also probably the most complicated, most emotionally charged and affect people, more than ‘things’…

Practitioners have to deal with distressed clients, angry clients, aggressive oppos and vulnerable children…the last thing they need is to be told they are not good enough..

Maybe LS’ motives for making these statements is based on the increase in LIPs due to withdrawal of LA?

The bigger question must be (in all cases): How does the client know that they have the best person for the job?