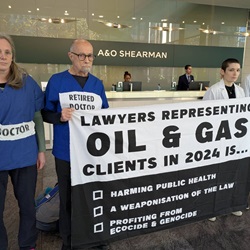

Doctors and scientists protest at A&O Shearman

It is “unlikely” that the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) would take regulatory action against a solicitor who refuses to work on fossil fuel matters for reasons of conscience, counsel’s opinion has declared.

The opinion was delivered to the senior partners of the five ‘magic circle’ firms – A&O Sherman, Clifford Chance, Freshfields, Linklaters and Slaughter and May – on Friday as part of the latest action by the campaign group Lawyers Are Responsible (LAR), which is urging big practices to stop work on fossil fuel projects.

They were joined by around 50 doctors and scientists, who were questioning the role of lawyers in the climate crisis as legal advisors to and representatives of the fossil fuel industry.

The 45-page opinion from Claire McCann and Hana Abas of Cloisters Chambers assessed the consequences of lawyers refusing work connected with fossil fuel extraction, blowing the whistle in respect of their employers, clients or third parties, and exercising their right to peaceful protest outside of their workplace.

For ‘conscientious objectors’ to handling fossil fuel-related work, the opinion said, belief in the climate crisis and the moral duty to avoid catastrophic climate change would potentially be protected under article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion) and also discrimination law.

This would mean lawyers could not be unlawfully discriminated against, harassed or victimised because of those beliefs, so long as they have manifested their beliefs in an “appropriate way” and there was a sufficiently close and direct connection between their refusal to do the work and their beliefs.

Regulatory action against solicitors would need to be justified as an interference with article 9.

The barristers said it was “unlikely that the SRA would seek to take regulatory action in respect of a solicitor who refuses work”, given that the Law Society’s guidance last year on the impact of climate change on solicitors said solicitors may legitimately place weight on climate-related concerns when deciding whether to accept/advise a client.

The SRA said it was “supportive” of the guidance but that it should not be interpreted as its regulatory position.

The opinion went on: “It is possible that the manner in which an individual refuses particular work could give rise to an arguable breach of the SRA principles.

“For example, if in the course of refusing work for a fossil fuel company, a solicitor made public, personal criticisms of individuals who do accept work from fossil fuel companies, this might give rise to an arguable breach of the requirement to act in a way that upholds public trust and confidence in the profession.

“The SRA would need to show, on the facts, that a legitimate aim (probably the upholding of professional conduct standards) was engaged on the facts, and that any disciplinary sanction pursued was proportionate and necessary in pursuing that legitimate aim.

“It is possible that the manner in which an individual refuses the work (e.g. public criticisms on social media) may be distinguished from the actual refusal and may be done in such a way to undermine public trust and confidence in the profession.

“In these circumstances, the SRA would have to show that any disciplinary sanction was proportionate and necessary.”

For barristers, the cab-rank rule was a regulatory hurdle. One exception is that a barrister must refuse instructions where there is “a real prospect that [they] are not going to be able to maintain [their] independence”.

Independence in this context may well mean independence from external pressures, rather than moral convictions, however, the opinion cautioned.

“Our view at present is, therefore, that the [Bar Standards Board] is likely to consider most acts of conscientious objection (where services are withheld) to involve a potential breach of the cab rank rule, but that it is possible that [this exception] could be found to apply in individual cases.”

For an “overt, proven breach” of the cab-rank rule, the opinion said it would be “relatively straightforward” for the BSB to overcome article 9 on the basis that action was required for the legitimate aim of upholding professional conduct obligations.

At the same time, “deliberate breaches of the cab-rank rule may not be apparent and/or could be difficult to prove, rendering the prospect of regulatory action, in practice, somewhat remote”.

For those blowing the whistle for climate-related reasons, protections would apply to ‘workers’ – ie, solicitors and partners in law firms – but not self-employed barristers, the opinion said.

Legal professional privilege did not apply as an exemption from the protections for whistleblowers where the advice was sought by the client to further a crime, fraud or similar – and which could include an environmental crime.

Disciplining an employee for the mere act of attending a peaceful climate-related protest was unlikely to constitute a justified interference with their human rights by their employer or chambers.

In the event of a criminal conviction, “the need to uphold public trust and confidence in the legal profession and the risk of harm to an employer’s reputation are likely to constitute legitimate aims”.

But the question of whether such action was necessary and proportionate in pursuit of those aims would depend on matters such as the gravity of the offence, the extent to which it caused or risked harm to the public, and the extent to which it involved damage to property.

Lawyers Are Responsible teamed up with doctors and scientists at all of the magic circle firms

LAR said it would be building a campaign to educate staff about these issues. It has also prepared an executive summary and worked scenarios for use as a teaching tool in law schools and universities.

Dr James Dyke, associate professor in earth system science, and assistant director of the global systems institute at Exeter University, was among those protesting at the law firms last week.

He said: “Lawyers play a crucial role in the exploitation of new oil and gas. This includes creating and administering the legal contracts related to the finance and management of fossil fuels extraction.

“With record-breaking global temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions, we now need to rapidly phase out fossil fuels. This means we must leave fossil fuels reserves in the ground.”

Leave a Comment