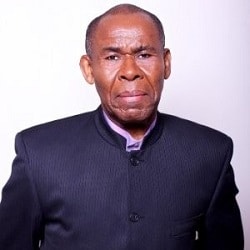

John: Culture change needed

The Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) spends too much time on diversity training and monitoring, and not enough on assuring that its enforcement staff act in a non-biased way, it has been claimed.

Professor Gus John warned that “you cannot right racial wrongs by doing wrong things more competently”, and said the SRA needed to rethink its approach.

He urged the SRA to employ experienced solicitors, rather than former police officers, to conduct investigations into law firms.

Professor John was commissioned by the regulator in 2014 to review why people from a Black, Asian and minority ethic (BAME) background featured disproportionately in its regulatory processes.

He found it was caused by broader socio-economic factors around access to the profession, and not discrimination by the regulator, but speaking at a webinar organised this week by the law firm Leigh Day, he expressed disappointment that the situation has not changed much, to judge by a report the SRA published in December.

The academic said he still had solicitors asking him to intervene in investigations conducted by the SRA and, where appropriate, he did write to it on their behalf.

“More often than not, one finds that the supervisor is acting in the most absurd manner,” he said. “The pressure they place on people is really quite extraordinary.”

He was critical of the SRA’s focus on diversity and unconscious bias training, and “counting numbers”, when it should be monitoring and quality assuring the work of individual supervisors, who he said were afforded “a huge amount of discretion”.

Professor John said a lot of the SRA’s investigators were former police officers who “brought a particular culture to the task”.

He argued that it would be better to train up experienced solicitors to conduct inspections into firms. “We need to find those teams that the profession itself can have greater confidence in than the people who now go from the SRA into firms,” he said.

There was, he concluded, a need for cultural change at the SRA and a focus on “structural and people issues”.

Ranjit Sond, president of the Society of Asian Lawyers, agreed that despite various reports on the issue over the years, “nothing has really changed” and there needed to be more work on how the SRA’s policies were applied in individual cases.

The fact that one of the SRA’s suggestions for future work was to introduce an in-house arm’s-length quality assurance team “indicates they’re not doing this [now]”, he noted, adding that ideally it would be an external team.

But he praised the SRA for actively reaching out and listening to groups such as his, and said the debate had to be wider that just looking at the regulator. Other speakers agreed that there were societal issues at play too.

Gideon Habel, a partner and head of Leigh Day’s regulatory and disciplinary department, said the data the SRA published last year was insufficient to support the suggestion that its processes did not exacerbate the disproportionality identified, because it did not show whether the underlying allegations were comparable.

He added that it would help solicitors challenge the SRA if it reinstated regulatory defence costs as falling within the mandatory scope of solicitors’ insurance policies. It removed them in 2010.

Angela Latta, head of performance and oversight at the Legal Services Board, praised the SRA for its “intensive focus on diversity” and said it did “a good job in helping to address inequalities in the sector”.

She observed that regulators in other sectors faced the same issues of disproportionality.

Speakers highlighted the need for greater support of smaller law firms, where BAME lawyers work in disproportionate numbers; this has long been put forward as one of the causes of the enforcement problem.

But Ms Latta said “supporting and nurturing” small firms was not a regulatory matter. “This is something the Law Society needs to step up… as a representative body.”

Leave a Comment