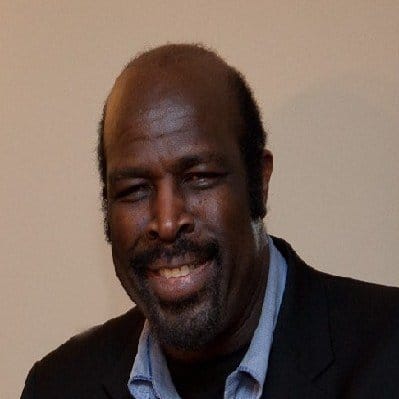

Crawford: Very substantial mitigation

The High Court has rejected one of the Bar Standards Board’s (BSB) first appeals against a disciplinary sanction, sharply criticising the way in which it was pursued.

The court found that the BSB had “fallen far short” of showing that no reasonable tribunal could have decided to just reprimand high-profile barrister Lincoln Crawford over his breach of a restraining order.

The disciplinary troubles faced by Mr Crawford all stemmed from an acrimonious end to his second marriage and continuing friction with his ex-wife and her new partner over access to the children of the marriage.

The barrister is a one-time employment judge and recorder, and a leading anti-discrimination campaigner who was awarded an OBE in 1998.

In 2006, the barrister was convicted of harassing his ex-wife and her partner, resulting in a conditional discharge for 18 months, and made subject to a restraining order limiting his contact with them.

Two years later, he was convicted on one charge of breaching the restraining order, and was sentenced to a community order with 50 hours’ unpaid work.

The BSB brought charges as a result. He pleaded guilty over the breach, but a disciplinary tribunal found him not guilty over the harassment convictions.

In the circumstances of the breach – for which the tribunal found his ex-wife “largely responsible” – it issued a reprimand, saying it considered Mr Crawford was “most unlikely to offend again”.

In 2015, however, the barrister was convicted of six counts of breaching the restraining order with 29 text messages (out of 446 he sent her over a six-month period in 2013), an email and a letter. He was sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment, suspended for 24 months, with 150 hours of unpaid work and costs.

Hickinbottom LJ noted that his ex-wife sent texts “in similarly unkind and rude language – although she, of course, was not the subject of a restraining order”.

This led to more BSB action, during the course of which the regulator asked Mr Crawford for an undertaking to suspend himself from practice during the disciplinary process, including any appeal, failing which the BSB said it would consider applying for an interim order to suspend him.

Hickinbottom LJ said: “On the basis that, in practice, he had no choice… the respondent gave that undertaking, and he has consequently not practised since July 2015.”

The case reached a tribunal in June this year, which again issued a reprimand, saying that, but for the self-suspension, it would have imposed an 18-month suspension, reduced to 12 months because of various mitigating factors.

These included the fact that there had been no repetition of the conduct for four years. “We are confident that there will not be any more because of the ages of the children, who are now 18 and 16,” the tribunal added.

The High Court said the test on the BSB’s appeal was whether no reasonable disciplinary tribunal could properly have imposed the sanction of reprimand that this tribunal did.

Hickinbottom LJ’s “firm view” was that it fell within the range of sanctions properly open to the tribunal.

He found that the tribunal properly took into account the seriousness of the charge against Mr Crawford, as well as the “very substantial mitigation” he put forward – “including his professional achievements and public service; his early admission of, not only the facts, but that what had occurred amounted to professional misconduct; and his full cooperation with the BSB”.

The judge said: “His culpability was substantially reduced by the fact that, as found by the tribunal, the conduct which formed the basis of the criminality occurred in circumstances of high emotion, typically as heat of the moment responses to disagreeable texts from [his ex-wife]; and the fact that there had been no incident or complaint for four years.”

Hickinbottom LJ observed that, as serious as the criminal convictions were, “the tribunal was entitled to conclude that his culpability was considerably diminished by these factors. Its conclusion does not become perverse simply because the BSB does not agree with it”.

That the first tribunal had expressed what turned out to be misplaced confidence that Mr Crawford would not reoffend did not mean the latest one had been wrong to have the same confidence – it had noted the “substantial change of circumstance since 2009”.

“Furthermore, [Mr Crawford] had been the subject of a self-suspension for nearly two years, at considerable personal cost, the tribunal recording that he was, as a result, in ‘a very poor financial state’. This was clearly a factor to which the tribunal gave considerable weight. It was entitled to do so…

“In my judgment, the sanction imposed fell well within the appropriate range open to the tribunal.”

The court was highly critical of the way the BSB had presented its case, saying: “The grounds of appeal in this case singularly failed to identify the issues that were said to arise, and to which argument would be directed. However, that failure was compounded by their failure properly to engage with the grounds of appeal available under [the BSB rules].”

He added: “Nothing filed or served by the BSB suggested what a reasonable sanction in the respondent’s case might have been.”

The court added a postscript with guidance on how the BSB should pursue such appeals in future.

“Clarity in the BSB’s case is important, not just to assist the court, but, crucially, to enable the respondent, whose sanction the BSB is seeking to increase, to know the case he is facing and to have a fair opportunity to respond to it.”

A BSB spokesman said: “We note and take on board the comments of the court in this case and will be considering them.”

Leave a Comment