The disproportionately high representation of black and minority ethnic (BME) solicitors in the Solicitors Regulation Authority’s (SRA) disciplinary work is caused by broader socio-economic factors around access to the profession, and not discrimination by the regulator, a major independent report has concluded.

However, equality and race relations expert Professor Gus John said the SRA needs to “look very carefully and urgently at how sole practitioners and small firms are regulated”.

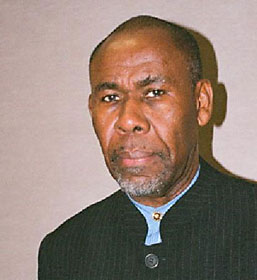

Professor John was appointed in August 2012 to investigate the longstanding issue of disproportionality, which triggered the 2008 Ouseley report. As part of it, he also reviewed six cases where BME solicitors had specifically alleged discrimination – some with the vocal support of the Society of Black Lawyers – and found “no evidence” to support such claims.

His work involved 160 detailed comparative case reviews (split equally between BME and white solicitors), a statistical analysis of SRA data, and surveys, focus groups and interviews with a range of individuals and groups.

The 238-page report said that the disproportionality clearly found at various stages of the regulatory process should not be “immediately interpreted as evidence of discrimination or racism on an institutional level”.

Professor John said a number of factors rendered BME practitioners and small firms more vulnerable to regulatory action than their white counterparts. The main reason was that BME solicitors are more likely to work as sole practitioners or in small firms, which generate more regulatory action than larger practices.

The BME solicitors investigated had established sole practices with six years’ post-qualification experience, compared to 19 years for white solicitors. “Less experienced sole practitioners are more likely to fall foul of SRA regulation as they lack the resources to both ensure best practice is always followed and to insulate themselves against investigation,” he said.

There are wider socio-economic reasons BME solicitors end up in small firms, he suggested, as the greater difficulties many face in going to top-notch universities – because they are “less likely to come from backgrounds of privilege” – mean “they lack the advantages enjoyed by other demographics when it comes to progressing in an elite profession such as practising law”.

Professor John explained: “These advantages relate not only to the standard of education received, but also to the formation of a network of elite associates that might be useful in providing access to opportunities and resources later, and to a pronounced understanding of how to navigate elite systems so as to advance one’s career…

“A BME solicitor, lacking the benefits and social and cultural capital outlined above, may be directly or indirectly disadvantaged when seeking training contracts and/or employment with established and well-resourced law firms.

“Frustrations and limitations in career opportunities may result in a BME individual working for smaller firms or deciding to advance their prospects by starting sole practices, relatively soon after qualifying.”

Another factor could be that BME solicitors may choose to establish practices aimed at serving BME communities, where particular cultural practices could affect the normal running of their firms.

Professor John made 50 recommendations for consideration by the SRA, Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal and Law Society. He told Legal Futures that the SRA’s approach had to be “more nuanced” to recognise that one size did not fit all.

He said the SRA put the regulatory objective of “protecting and promoting the public interest” above all the other objectives in the Legal Services Act – although “I’m not sure they understand what the public interest is” – and this needed to change.

BME solicitors often set up firms in their communities to provide access to justice, for example: “If you don’t have a concern about the extent to which the way you regulate affects access to justice, then you are not regulating in a sensible manner.”

This meant that while there were certain “red lines” – such as the sanctity of client account money – he suggested the SRA should be more sensitive to the impact of cultural practices on other apparent rule breaches where there may be “no public interest value” in pursuing them.

Professor John said the SRA had made considerable strides in recent years since the Ouseley report of 2008, but it had “not moved enough” on its own equality and diversity, particularly in terms of recruitment practices. But he praised new chief executive Paul Philip for committing to lead the SRA’s response to this.

He was critical of those BME solicitors who had claimed discrimination in the cases he examined. “If you alight upon cases where people bring charges of discrimination only after the determination has been made, it suggests you are trying to find reasons why you should be resisting the outcome… The issues are too important for people to use them vexatiously.”

Mr Philip said: “Disproportionality of outcomes for BME lawyers is, unfortunately, not confined to regulatory outcomes. The report identifies that there is not a simple, single, cause of this disproportionality and, similarly, there is not a single, simple, solution. Therefore addressing the issue will need the help and engagement of a wide range of individuals and organisations.

“Building on the previous body of work on this subject, we now have a better understanding of the challenges we, and others, face. We will take a short period of time to consider this comprehensive report, and use that time to engage and discuss these issues with a range of interested individuals and organisations. Our aim is to provide a full, public, response by the end of May.”

The full report can be found here.

Leave a Comment