Posted by Neil Rose, Editor, Legal Futures

Posted by Neil Rose, Editor, Legal Futures

The Legal Services Board’s call last week for an “open debate” on the cost of regulation will not have gone down a storm at Chancery Lane, I’d wager. The part of the practising fees most under threat from such a conversation is surely the 24% that goes to the Law Society for work that is essentially representative in nature but seen as being sufficiently in the public interest for solicitors to fund via compulsory levy. For now, anyway.

The genesis of these so-called permitted purposes – an issue which, it should be said, affects all of the regulators where the body separately does representative work – dates back to the late 1990s and an aggressive advertising campaign run by the Law Society against the Access to Justice Bill. Out of nowhere a backbench Labour MP with no connection to the law laid an amendment to the bill to restrict what activities the Law Society and other legal bodies could apply practising fees towards. It was seen as Lord Irvine’s retribution for a campaign he did not like.

As it happens, it proved a shot across the bows in the main. Though the concept was introduced, the permitted purposes were drawn sufficiently widely that a good proportion of the society’s work was covered by them, with the rest paid for by commercial income. But since then the possibility of the tap being turned off entirely has hung over Chancery Lane and the others.

Imagine the day when your practising renewal comes up and the form contains a section where you have to choose whether to make a voluntary contribution towards the representative work of the Law Society. How many of the 125,000-odd solicitors would do so? How many solicitors think they get value for money from the society? To judge by contributors to the Gazette’s website, many solicitors consider it a waste of money.

Imagine the day when your practising renewal comes up and the form contains a section where you have to choose whether to make a voluntary contribution towards the representative work of the Law Society. How many of the 125,000-odd solicitors would do so? How many solicitors think they get value for money from the society? To judge by contributors to the Gazette’s website, many solicitors consider it a waste of money.

In particular do the largest law firms, which employ something like 40% of all practising solicitors, feel they get enough? I’d suggest they do not, aside from the work done by the international department, particularly on opening up overseas markets. They feel the City of London Law Society could do the job perfectly well.

So what does the Law Society do for you? I have long been impressed by the work of the society’s specialist committees, which beaver away with little publicity on issues of importance to the profession and the law in general. They are a jewel rarely polished and probably more effective in lobbying government than the society more widely on the ‘big’ issues – when it came to legal aid reform and the Jackson changes, the Law Society, along with everyone else considered to be in the claimant lobby, was largely ignored.

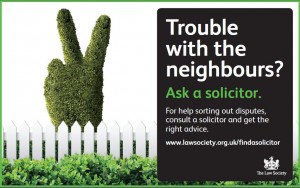

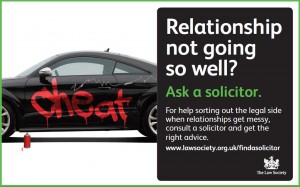

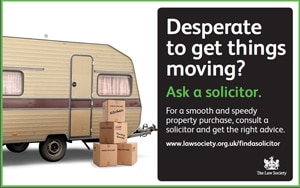

More high profile is the society’s annual autumn advertising campaign, which this year – as the pictures on this page show – is trying to be a bit more controversial than in the past. This has the dual purpose of promoting the profession, of course, and also of showing solicitors that the society is out there fighting for them. I know some people don’t like them, but I find them more eye-catching than previous efforts, most infamously ‘My solicitor, My hero’ (which was a bit of a publicity stunt, in truth).

More high profile is the society’s annual autumn advertising campaign, which this year – as the pictures on this page show – is trying to be a bit more controversial than in the past. This has the dual purpose of promoting the profession, of course, and also of showing solicitors that the society is out there fighting for them. I know some people don’t like them, but I find them more eye-catching than previous efforts, most infamously ‘My solicitor, My hero’ (which was a bit of a publicity stunt, in truth).

Where the society gets into stickier territory is areas like the Conveyancing Quality Scheme (CQS), which it is planning to replicate in the private client arena. Should the society be telling lenders that they should only work with those of its members who have paid to join its special scheme? But maybe the alternative for members is even worse without CQS. And what about the sections, which again require further payment to join.

CQS looks like a sign that the Law Society is, quietly, preparing for a future where it receives no compulsory subsidy and has to live on what it can raise from members. It can do this by trying to persuade solicitors to pay into the pot voluntarily and/or through selling products and services that the profession actually wants and values. Making enough from the latter certainly sounds more appealing, and also means that it need not do the former, given that it is quite possible that many, many thousands of solicitors would choose to pay nothing. (Mind you, the Bar Council asks members to pay an extra membership services fee to support its non-permitted purposes work and around 80% of private practice barristers and 50% of employed barristers pay it – but then maybe the Bar is a bit more united than the solicitors’ profession, although these figures are falling.)

Remember that membership of the society is not compulsory if you want to be a practising solicitor – you still pay the fees and are regulated by the SRA come what may. It’s one thing to choose to be a member if it’s free, but another if it’s going to cost every year. If membership halved, say, both the Law Society’s authority and its commercial power would be substantially weakened. Perhaps that is why it continues to look at ways of bringing paralegals and other non-solicitors more into the fold.

Remember that membership of the society is not compulsory if you want to be a practising solicitor – you still pay the fees and are regulated by the SRA come what may. It’s one thing to choose to be a member if it’s free, but another if it’s going to cost every year. If membership halved, say, both the Law Society’s authority and its commercial power would be substantially weakened. Perhaps that is why it continues to look at ways of bringing paralegals and other non-solicitors more into the fold.

The debate is just starting and there is a long way to go before it is resolved. I certainly wouldn’t bet against the levy becoming voluntary eventually, so maybe it is just as well that the Law Society and others will have plenty of time to prepare for it.

Leave a Comment