Sumption: law firm had not assumed responsibility for decision

The Supreme Court has upheld a ruling that a law firm which had been negligent in drawing up a loan facility agreement was not legally responsible for their client’s decision to actually make the loan.

The decision has been branded as good news for solicitors, who “no longer appear to be expected to underwrite claimants’ risks and business ventures”.

In BPE Solicitors & Anor v Hughes-Holland (in substitution for Gabriel) [2017] UKSC 21, Mr Gabriel, a very wealthy businessman, made a £200,000 loan to a close friend, Mr Little and one of his companies, in connection with the development of a disused heating tower in Gloucestershire. Mr Gabriel assumed that the money would be used to finance the development, although this was not expressly stated by Mr Little.

In fact, the building belonged to a company, High Tech, subject to a charge in favour of a bank, securing a loan of £150,000. Mr Little intended to transfer the property to a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which would use Mr Gabriel’s funds to pay High Tech, which would use them to discharge the loan and charge.

The judge subsequently held that Mr Gabriel knew nothing of these plans, and he would not have signed the loan documentation had he done so.

Mr Gabriel instructed Cheltenham law firm BPE to draw up a facility letter and a charge over the building. He used a template from an earlier abortive transaction, stating that the loan money would be used to assist with development costs. He thereby unintentionally confirmed Mr Gabriel’s incorrect understanding of Mr Little’s plans.

The transaction failed and Mr Gabriel lost all his money. He sued Mr Little, High Tech and the SPV for fraud and negligent misrepresentation, and BPE for dishonest assistance in a breach of an implied trust and for negligence.

At first instance, the judge dismissed all the claims except the negligence claim against BPE, holding that it should not have included the reference to the proposed use of the loan in the documentation and should have explained to Mr Gabriel that in reality the money would be applied for the benefit of Mr Little or his companies.

The Court of Appeal allowed BPE’s appeal and held that the whole loss was attributable to Mr Gabriel’s misjudgements and reduced to the damages to nil.

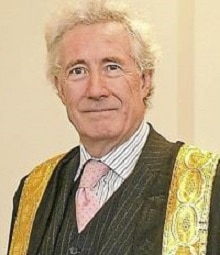

Lord Sumption, giving the ruling of the court to uphold the Court of Appeal’s decision, said it was clear that BPE had not assumed responsibility for Mr Gabriel’s decision to lend money to Mr Little.

“Their instructions were to draw up the facility agreement and the charge, nothing more. Mr Spencer did not know and did not need to know what had passed between Mr Gabriel and Mr Little, except that they had agreed upon a loan of £200,000 secured by a charge on Building 428.

“He knew nothing about the nature of the proposed development, its likely cost, the financial capacity of Mr Little to fund it without Mr Gabriel’s loan or the value of the property in its developed or undeveloped state. Indeed, he does not even appear to have known of Mr Gabriel’s assumption about the use to be made of the loan moneys.

“He simply included in the draft facility agreement by oversight language which by an unhappy chance confirmed that assumption.”

Lord Sumption continued that even if the assumption about the use of the loan had been right, “Mr Gabriel would still have lost his money because the expenditure of £200,000 would not have enhanced the value of the property… None of the loss which Mr Gabriel suffered was within the scope of BPE’s duty.

“None of it was loss against which BPE was duty bound to take reasonable care to protect him. It arose from commercial misjudgements which were no concern of theirs.”

Rhian Howell, a partner in the Bristol office of Beale & Company, the solicitors for BPE, said the ruling improved on the House of Lords’ SAAMCO ruling in 1997.

She said: “Unless it can be said that the professional was retained and gave advice on whether a claimant should enter into a transaction, the ‘no transaction case’ is now truly dead.

“Indeed, if a professional defends a claim on the basis that the wrong information complained of by a claimant has not caused the losses, the burden is now on the claimant to prove that.

“This decision has not only narrowed the exposure for professionals, it has made it much harder for claimants to pursue their claims. We finally have a position where professionals no longer appear to be expected to underwrite claimants’ risks and business ventures.”

Leave a Comment