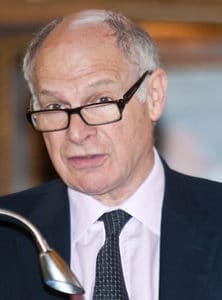

Neuberger: drop discovery and cross-examination in small claims

“Quick and dirty” online dispute resolution (ODR) is better than “no justice or absurdly over-priced justice”, the president of the Supreme Court has said in a wide-ranging speech that included a devastating critique of legal aid policy over the past two decades.

Lord Neuberger – who retires later this year – was blunt in his assessment that “things took a wrong turning in civil legal aid in 1999 and we have all been busy hoping or even trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again – but like all the King’s horses and all the King’s men, I am not sure that we can do it”.

In his speech to the Australian Bar Association biennial conference in London this week, he also criticised the government for the “lamentable” failure to keep the website containing UK legislation updated.

Lord Neuberger said the use of ODR for small civil claims would lead to “more imperfect justice than traditional systems of resolving disputes in court”, but resolution of disputes should be “proportionate” to the issues involved.

“There are many cases where there is a bona fide dispute between parties about a sum of money which means quite a lot to both or one of them but in respect of which a trial conducted according to traditional principles would be wholly disproportionate.”

Lord Neuberger said it could not be right to say to parties that disputes could not resolved or only on the basis that “it will cost the loser legal costs more than 10 or 15 times the amount at stake and the winning party will probably be out of pocket too; and, while the state may be obliged to make legal aid available in principle, it would be equally wrong to expect the state to fund the litigation on that basis.”

He went on: “The only solution is for the legal system to provide a dispute resolution mechanism which is cost-effective, a system which is, to borrow an expression used by valuation accountants, quick and dirty.

“In a phrase imperfect, but accessible and affordable, justice: it’s better than no justice or absurdly over-priced justice.”

Lord Neuberger said that if small claims ended up going to a hearing, there was “much to be said for dispensing with those two hallowed features of common law civil litigation, discovery and cross-examination”.

He went on: “So far as discovery is concerned, I am sceptical about the notion that many cases are decided by a ‘smoking gun’ found on the often enormously time-consuming and expensive exercise of disclosure and inspection of documents, and in any event it is questionable whether the odd case where full disclosure really has made all the difference justifies the pointless expenditure in the countless other cases where it makes no difference.

“As for cross-examination, there is force in the contention that most of the best points that emerge from questioning can be made much more shortly in argument, and I am unpersuaded that there is any real force in the notion that it enables the judge to benefit from his or her impression of a witness.

“Sometimes it seems to me that factual disputes are resolved by reference to the better-performing witness, not the more honest witness, and I think that, at least in some cases, it may be safer to assess the evidence without the complicating factor of oral testimony.”

Going further than before in acknowledging the potential of artificial intelligence, Lord Neuberger commented: “It is no longer fanciful to think that artificial intelligence will be able to do the job of lawyers and judges better than humans.

“I use my words carefully, because I am not saying it will happen; merely that it is not fanciful to think that it will happen.”

The president referred to the success of computers in beating the world champion chess player and “recent reports” that champion poker players were suffering the same fate.

“Clearly the involvement of AI in legal advice and representation, and indeed decision-making, could have enormous cost and efficiency implications – and many other equally far-reaching consequences.”

Lord Neuberger said it was “peculiarly ironic” that access to legal advice was contracting “at a time when we have never been more concerned to ensure that all citizens enjoy rights”.

He said: “It verges on the hypocritical for governments to bestow rights on citizens while doing very little to ensure that those rights are enforceable. It has faint echoes of the familiar and depressing sight of repressive totalitarian regimes producing wonderful constitutions and then ignoring them.

“Quite apart from human rights, the increased complexity of legislation and the substantial growth in regulation makes it harder than ever for non-lawyers to work their way through to establishing what their rights and duties actually are. Thus the growth in complexity and in regulation renders the need for access to legal advice all the greater than it ever was.”

Tracing the problem back to the “flag-wavingly named” Access to Justice Act 1999, he said the changes over the past 20 years in civil and family legal aid “have resulted in many people being faced with the unedifying choice of being driven from the courts or having to represent themselves”.

Lord Neuberger continued: “Many people, including me, feel that things took a wrong turning in civil legal aid in 1999 and we have all been busy hoping or even trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again – but like all the King’s horses and all the King’s men, I am not sure that we can do it.

“The sad thing is that the 1999 Act was introduced on the back of an assertion that civil legal aid cost too much, and, quite apart from the fact that there is reason to doubt some of the figures on which that assertion was based, one wonders whether that concern could not have been met by increasing damages in 1999 on terms that where a legally aided claimant received damages, he was required to pay the increase to the legal aid fund.

“But I fear that it is 20 years too late to turn the clock back to reincarnate the philosophy underlying the 1949 Act which was that ‘no one will be financially unable to prosecute a just and reasonable claim or defend a legal right’…

“In the end, the question whether the government should make large amounts of money available to enable ordinary people to get access to justice may depend on one’s view of the argument that access to justice is a special case when it comes to government responsibility.”

So far as statutes and statutory instruments were concerned, Lord Neuberger said the UK government did well in ensuring that new statutes are available on the legislation.gov.uk website “reasonably promptly”.

“However, the updating service to deal with amendments and repeals is little short of lamentable, with amendments and repeals sometimes not being recorded more than six years after the event.

“It should not cost much for the UK government to ensure that its legislation website is kept up-to-date, so that current legislation is freely available to everyone.”

Leave a Comment