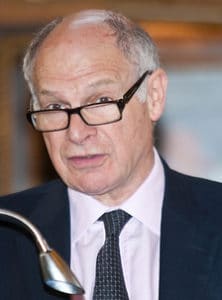

Online dispute resolution (ODR) could be the only way of ensuring access to justice in moderate-sized claims in future – but the Bar Council is trying to find an alternative that retains hearings, according to the president of the Supreme Court.

Lord Neuberger noted the work being done on ODR by Lord Justice Briggs and the Civil Justice Council working party headed by Professor Richard Susskind, and said that ultimately, an eBay-style system might be the only solution.

“With the high cost of traditional litigation and the shrinking of legal aid for civil cases, it may be the only realistic and proportionate way of achieving access to justice for ordinary people with moderately sized claims,” he said in the keynote address last week to a conference on IT and the law held by the British Irish Commercial Bar Association Law Forum.

However, the judge revealed that “in the search for an alternative”, the Bar Council has set up a committee to look at ways to maintain traditional hearings for moderate claims, but at a lower cost.

He said that if the outcome was successful, it would still be a “victory for technology” – first because IT would inevitably be involved in any solution.

“Secondly”, he continued, “it appears that it was, at least in part, the threat of an ODR system which prodded the Bar Council into appreciating that they had better do something.”

Lord Neuberger went on to tackle the issue of video technology in courts – as is now present in Supreme Court hearings. He said: “If the public has the right to see, and to be told about, what goes on in the courts, why should we not allow cameras into the courts, so that the public can watch court hearings as they happen streamed into their living rooms or offices?

“It could be said with some force that this is merely the technological extension of the traditional public right to come into court physically. I see no satisfactory answer to this argument so far as hearings without witnesses and juries are concerned.”

However, where juries or witnesses were involved it was “obviously more difficult”, he said, continuing: “Vulnerable, even shy or nervous, people may not be prepared to give evidence, or may not give a good account of themselves if they are being filmed.

“And there is a risk of some witnesses, or even some lawyers… playing to the gallery. Furthermore, in some cases filming may increase the risk of witness or jury intimidation.”

He argued that as a judge his behaviour had been unaffected by moving from the “unfilmed Court of Appeal to the filmed Supreme Court”.

Equally, where no witnesses were present, video-link evidence could be more widely used, he suggested, giving the example of lower value Privy Council cases which could be made cheaper by avoiding the need for advocates to travel to London: “I am unconvinced that evidence by video-link puts anybody at much of a disadvantage at least in a civil case, provided that it is properly supervised.”

Even in criminal cases, he went on, “there must be a powerful case for saying that it should be routine for people in custody pending trial to appear via video-link from prison on interlocutory matters, as now often happens”.

However, he expressed concern at “evidence, which may not be statistically wholly reliable, which suggests that juries may be less likely to convict on the basis of evidence given by video than on the basis of live evidence”.

Turning to the trial process, the judge predicted that hearings involving purely electronic records without hard copies “seems to me to be likely to become the norm, maybe even the invariable practice, in due course”. Meanwhile, the electronic filing of documents should become routine, “at least in big cases”, he added.

Leave a Comment