By Christopher Sexton, investment director at Saunderson House

By Christopher Sexton, investment director at Saunderson House

Our note to clients in July began with a quote from a John Wayne western, ‘It’s quiet…too quiet’. That wasn’t supposed to be a complaint. Entitled ‘Wrestling with Bears’, the note tried to address why so many investors, economists and commentators continued to nurture deeply negative views towards equities despite the economic recovery and strong rebound in share prices since the financial crisis. Complaint or not, it is no longer quiet. In this brief update we attempt to unpick the drivers of recent volatility, including a disturbing 8.3% decline in the UK’s FTSE 100 Index in the past six days, and tackle the all-important question – where next for markets?

Let us begin with some context – a brief UK stock market history since we published the ‘Wrestling with Bears’ note. In late July the FTSE 100 stood just shy of 6800. It had made little progress in the calendar year to that date, but, as hinted by our ‘too quiet’ quote, neither had it suffered any periods of significant weakness. This calm gave way to volatility in early September with the index suffering a near 10% slide in six weeks, taking it below the 6200 level. At that time, we published a brief note, ‘Bear Hug’, urging clients to look through the volatility and shares did indeed rally all the way to 6750 by late November only for the recent weakness to take us back below 6200 last night.

So much for the history; what about rationalising these moves? What seems to be worrying markets most this time is a precipitous decline in the oil price. As the chart below shows, the weakness has indeed been marked, comparable in magnitude to the fall during the financial crisis. While cheaper oil was initially welcomed as a boon to consumers the world over, the break-neck pace of the decline has now begun to unnerve investors. Another recent development is also gnawing at confidence. This is the continued weakness in eurozone economies that, together with very low inflation, is prompting concerns that continental Europe will not be able to avoid a prolonged slump. To tie this in with oil price weakness one need only consider that, perhaps, economic weakness is driving down demand for oil – and that this might be the key factor in explaining oil’s fall. This explanation is much less palatable than the supply side one, that the shale oil revolution in the US has driven supply up to the point where the energy market is out of balance.

It is from this perspective that Friday’s downgraded forecast for 2015 oil demand by the International Energy Agency might explain the further leg down in the oil price and the sizeable drop in equity markets on the same day. Add to this the continued weakness in the Russian rouble (see chart overleaf), that led the Central Bank of Russia to increase rates this morning from 10.5% to 17%, carrying with it the hint of renewed problems in emerging economies. There has also been price weakness in high yield bonds as investors grow concerned about the ability of some lowly rated oil producers to meet coupon payments given such low oil prices, and it becomes more understandable that there is a hint of crisis in the air.

Out of balance – oil price declines since mid-2014. The Russian rouble follows.

So how concerned should investors be about recent developments? Let us start by restating, in short form, our view of the world economy and broad investment thesis.

The world economy is struggling in the face of severe deflationary headwinds. Some of these, such as the overhang of consumer and government debt date from the global financial crisis, while others are secular developments, such as the expansion of the global labour force which is undermining wage growth, and advances in technology which are improving the efficiency of production and putting downward pressure on goods prices. More recently, advances in oil and gas extraction, termed the shale gas revolution, have added to deflationary forces. Faced with these headwinds policymakers have set interest rates at close to zero and resorted to unconventional monetary policies in an attempt to avoid a prolonged deflationary slump.

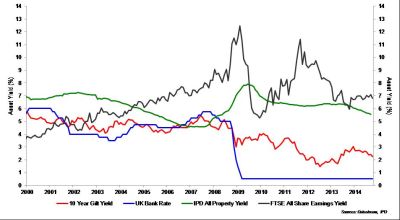

In response, risk averse investors have sought the safety of government bonds, forcing yields down to previously unheard levels. More value focused investors have bought corporate and other non-sovereign bonds for additional income and, as economic growth has picked up, property has also found favour. Finally, equities have recovered strongly since the financial crisis as they too yield more than government bonds and offer the prospect of dividend growth.

Our thesis on the macroeconomy and investment markets is useful in explaining recent developments. The success of anti-deflation policies is varied across the globe. The US is in the vanguard while the eurozone is very much to the rear, thanks to structural challenges and the need for peripheral nations to deflate rather than devalue their way back to competitiveness. Serial shortfalls in economic growth are bearing down on demand for oil, at the same time that technological advances are driving meaningful increases in supply. Price moves, as usual, are exacerbated by capital markets’ tendency to overshoot, thereby unnerving more investors and further magnifying price moves. The hint of crisis develops a life of its own.

However, reality always reasserts itself eventually. Lower oil prices, in aggregate, are good for global growth, a weaker euro is good for the eurozone and there are more policy steps to come from the Japanese and European central banks. Moreover, the US economy was already doing very nicely even before the additional boost from lower oil prices.

Our view as investors therefore is to observe developments but not be pushed around by them. It is interesting to note that some commentators who were worried that quantitative easing would inevitably lead to inflation are now concerned that deflation is unavoidable. The truth, in our view, is more prosaic. The debt overhang and deflationary headwinds are not issues with a one or two year lifespan. We are six years on from the financial crisis and still dealing with the fallout. It is likely that such issues will still be with us in one shape or form in another six years. With such long term trends playing out, it makes little sense to alter our investment views with every short term twist and turn in the road. We therefore maintain our preference for risk assets – equities and property – which continue to offer attractive yields versus nominal assets, such as cash and government bonds (see chart below). We recommend that clients take no action in response to the recent market volatility.

Four asset class yield model – equities and property attractive versus government bonds and cash

If you would like to discuss the contents of this note, or any other investment matter please call me on the number below, or contact your usual Saunderson House adviser.

Direct Dial: 0207 315 6506

chris.sexton@saundersonhouse.co.uk